"You Can't Time The Market!"

- havenlambert1

- Aug 22, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Dec 5, 2025

Read our latest white paper, co-authored by COO Michael J. Bennicelli, II, CFA and Managing Partner Stephen Weitzel, CFP.

Anyone who has worked with a financial advisor has certainly heard (and probably repeated) this mantra. At face value, this seems like a logical statement. No one can predict the future, so assuming you can make informed decisions about when to buy and sell is folly. Right? Well, as has been said, “it depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is”.

The term ‘market timing’ is defined as: “the act of moving investment money in or out of a financial market—or switching funds between asset classes—based on predictive methods.”1 The operative word here being predictive. The market timer is attempting to forecast (a fancy financial term meaning: to guess) the future direction of an investment and acting accordingly. Additionally, there is an implication that market timing involves short term decision making, frequent trading, and relies on gut instinct or intuition. While one may have success doing this over short periods of time, there have been few proven examples of long-term success using a pure market timing approach. Most investors and academics consider it to be impossible, and we at Reveille agree.

However, we do not believe, as many pundits and financial professionals do, that any strategy that adapts to changing market conditions should be labeled as “market timing.” The term is used as a pejorative to deride those who attempt to do other than buy, hold, and pray.

Statistics

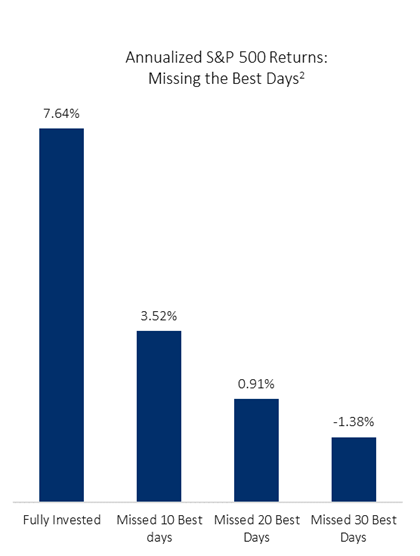

Many research pieces referencing 'market timing' often turn out to be statistical arguments against active management, centering around what might happen if you missed the best days in the market. A short Google search would reveal dozens of articles with precisely that conclusion: you shouldn’t actively manage a portfolio, because you could miss the markets’ best performing days. The statistical evidence they provide, such as the chart to the right, demonstrates how missing the best days kills your long-term return.

Although these studies abound, they are at best ill conceived, and at worst, intentionally misleading. Let’s examine a sample month in the S&P 500 to illustrate why that is the case.

March 2020, at the beginning of the Covid pandemic, was a particularly volatile month and stocks crashed. Ironically, two of the highest percentage return days in the history of the S&P 500 Index (3/13 and 3/24) occurred in this window of time. Yet, in order to miss these best days and participate in all other trading days (including poor performance days) would have required epically unreasonable portfolio gymnastics. An investor had to enter into Thursday, March 12 fully invested and been subject to the sixth worst daily return in market history. Aghast, they sell their position at the end of that day. Twenty-four hours later, after watching from the sidelines as the market rebounded over 9% in a single session, they changed their mind and bought back in at the end of the day on Friday, 3/13. This ensured they were exposed to modern “Black Monday”, the third worst day in market history. They wouldn’t give up their latest investment pursuit until a week later, when they sold out again, prior to Tuesday, 3/24. In doing so, they miss a 9.4% up day, ninth best in history. This is a recap of what would be required to miss just two of the best days in market history. In other words, to miss the 10, 20, 30, etc. best days in the market as one of these studies would suggest, you would have to be a MONUMENTALLY AWFUL market timer. Not very realistic, is it?

Source: Yahoo Finance

What about the counterfactual? What if you could time the market so well that you only missed the worst days? The data shows that returns improve dramatically (just look at the chart!) This is, like the prior argument, impossible to achieve. So, why aren’t there studies showing this data? Why is it not as widely circulated as the data that encourages passive investment? Bueller? As Mark Twain so eloquently put it, there are three types of lies: lies, damn lies, and statistics. This might be all three.

Doing Nothing

The conclusion one is encouraged to derive from these popular studies is that market timing is impossible, and you are better served to do the opposite: nothing! The term ‘market timing’ has become an industry dog whistle to force only one way of thinking – buy and hold; and there have been mountains of research evidence manufactured or misinterpreted to support it. Case in point, in 1986, Gary P. Brinson, Randolph Hood, and Gilbert L. Beebower authored a landmark paper entitled “Determinates of Portfolio Performance”. The goal of the paper was to study the attribution of portfolio returns amongst the pieces of the investment process: investment policy (i.e. asset allocation), market timing (i.e. tactical portfolio adjustments), and security selection. They conducted this analysis by comparing the returns of 91 large U.S. pension funds against hypothetical portfolios comprised only of indexes.

When this paper was published, the financial industry locked on to (and badly misconstrued) one of the findings in particular: the analysis showed nearly 94%3 of the variation within quarterly investment return was attributed to the asset allocation, or the mix of stocks, bonds, etc., while only 6% was attributed to market timing and security selection. The 94% number became a new gospel that proved the mix of assets drove returns, and that the pursuit of anything else wasn’t worth the effort. The premise was useful in marketing passive investment strategies and allowed investment managers and financial advisors to claim active management isn’t in their job description. Just buy/hold/pray. Fittingly, Hood was later quoted saying, “Nothing in the original paper suggests that active asset management is not an important activity. It was not the point of our paper, and our goal was not to demonstrate otherwise.”3

In our view, the results of this academic study have been bastardized to fit a convenient narrative. The disconnect comes from the fact that the industry has conflated the variability of quarterly returns with the actual long-term returns themselves. In fact, the study found that tactical investment adjustments made by the investment managers throughout the period compounded to produce meaningful impacts on their ten-year performance, and that the asset allocation alone could have contributed as little as 15% to the portfolios’ long term results.4

The Trend Is Your Friend

Can we reconcile that market timing is impossible, and active management is valuable? Yes, and the answer could be somewhat simple. Let’s reconsider the idea of missing specific market days for a moment. Examining when large up and down days typically take place, it becomes clear that most tend to cluster together in volatile periods that overwhelmingly take place during market downtrends. When markets go through significant drawdowns, the variability of returns tends to increase substantially – both up AND down.

Source: FactSet

For example, the period between September and December 2008 had some of the worst days in market history. Numbers 9, 10, 12, and 20 in terms of the worst ranked daily percentage loss on the S&P 500 Index to be specific. However, this period also boasted some of the best return days in market history (6 and 7). To have participated in those best days would have meant participating in one of the worst markets of all time. What if your investment objective, however, was to avoid being invested during market downtrends? And, by extension, that meant that you would miss both the markets’ best and worst days?

While we’ve already shown how improbable it would be to miss only the best or only the worst days in market history, something interesting occurs when you remove both. First, missing both the best and worst days meaningfully increases your returns over time; and second (maybe most importantly, in our mind), the amount of risk as measured by standard deviation decreases substantially. Why? It’s really just simple math. By removing large market movements, you end up with a smoother ride. Lower volatility, all else being equal, means fewer large drawdowns, and a greater benefit from compounding returns. Knowing these large up and down days generally happen during market downtrends, it seems obvious that the optimal strategy would be choosing not to be invested during market downtrends.

Source: FactSet

Fully Invested | Missed 10 Best & Worst Days | Missed 20 Best & Worst Days | Missed 30 Best & Worst Days | ||

Annualized Return |  | 7.64% | 8.11% | 8.33% | 8.84% |

Standard Deviation |  | 19.09% | 17.19% | 16.38% | 15.72% |

What’s the lesson in all of this? Asset allocation is important, but in our opinion, passive investment isn’t optimal. Don’t let emotion drive your decision-making. Definitely don’t try to predict or forecast. Market timing with any consistency is likely impossible. However, our contention at Reveille is that it is possible to discern a market’s primary trend; and our Rules Based Investment Discipline is designed to do just that. By aligning with those market trends, we aim to avoid large drawdowns and volatile market periods, seeking higher returns, while lowering risk. The trend, after all, is your friend.

Contact one of our team members in Florida or Georgia to learn more about how our process can prepare your portfolio for changing market conditions.

References

Investopedia – “Market Timing: What It Is and How It Can Backfire”, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/markettiming.asp

FactSet, Annualized price-only return of the S&P 500 from January 2004 – January 2024

The original study had a ~94% R-squared. This was retested and revised to ~92% in an update done 5 years later. https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2012/02/16/setting-the-record-straight-on-asset-allocation/

The Asset Allocation Hoax by William W. Jahnke, https://www.financialplanningassociation.org/article/journal/AUG04-asset-allocation-hoax

Disclosures

The S&P 500 is an unmanaged index of 500 widely held stocks that is generally considered representative of the U.S. stock market.

Inclusion of these indexes is for illustrative purposes only.

Indices are not available for direct investment. Any investor who attempts to mimic the performance of an index would incur fees and expenses which would reduce returns.

This is not a recommendation to purchase or sell the stocks of the companies pictured/mentioned.

The foregoing information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that it is accurate or complete, it is not a statement of all available data necessary for making an investment decision, and it does not constitute a recommendation. Any opinions are those of Reveille Wealth Management, and not necessarily those of Raymond James.

All opinions are as of this date and are subject to change without notice. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected, including asset allocation and diversification. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Individual investor's results will vary.

All investments are subject to risk, including loss. There is no assurance that any investment strategy will be successful. It is important to review the investment objectives, risk tolerance, tax objectives and liquidity needs before choosing an investment style or manager.

Comments